How to catalyse collective decision-making

“In any organisation of human beings, people will tend to glom onto interpretations of reality that do not call for them to take personal responsibility for the problem” — Ronald Heifetz

How do organisations make better decisions in volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) environments? How do we nudge teams to engage in deep collective sense-making? What is the role of leadership when there are no easy answers?

If anyone wants an example of what a VUCA environment looks like, then what is happening in the world right now is the perfect case study:

Our world is Volatile. Conditions are changing rapidly, driven by uncontrolled transmission and new variants of SARS-CoV-2 emerging.

Our world is Uncertain. We are unable to see around corners with any degree of certainty. Will a vaccine-resistant variant send the world back into lockdown? When will certain borders open or restrictions lift? When will confidence return to the markets? Are we going back to the office, or will we adopt some sort of remote or hybrid work pattern?

Our world is Complex. There is a multitude of interacting forces at play. It’s not just the science of virology that is shaping strategy. The decisions that governments and institutions make introduce a layer of variables that generate more uncertainty. Will our workforce be mandated to have vaccinations or PCR tests? How will our people react to that? Will some quit? Will factions form that undermine collaboration?

Our world is Ambiguous. Uncertainty is exacerbated by unclear information. The data we receive is usually incomplete or distorted by factors such as bias, inaccessible language, paternalism, politics, bad actors, and a highly polarised media sphere. A spot survey I conducted with some executives recently revealed large differences in opinion about the ability of vaccinated people to transmit COVID-19, which is pretty important knowledge when determining return-to-office policies.

Decision making in VUCA conditions

It is extremely difficult to make good decisions in VUCA environments. But decisions need to be made. Organisations cannot just wallow in limbo.

The key takeaway from military strategy scholarship is that in VUCA conditions, no single individual has sufficient knowledge and situational awareness to adequately develop a coherent strategy. Leadership, by necessity, must be a collective effort.

The starting point for any strategy is to interpret the available data. In an environment of collective sense-making and decision-making, each of us needs to bring to the table what we know and what we think it means. One’s person’s interpretation of the data might be quite different from another’s. The goal is not to fight over whose interpretation is right but to see the data from each other’s perspective and allow that perspective to be integrated into an emergent whole, a sort of shared Gestalt view of the current state.

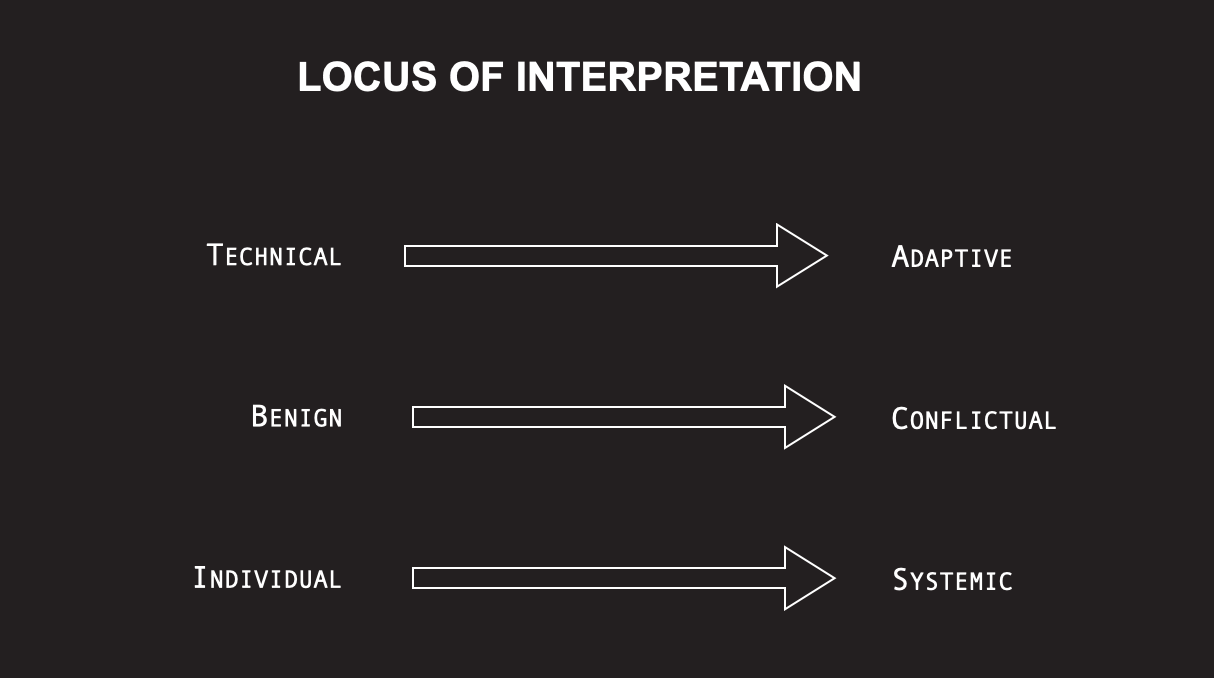

Ronald Heifetz, Marty Linsky, and Alexander Grashow propose that three important shifts of interpretation need to occur in order for people to effectively grapple with adaptive challenges.1

They argue that people need to be weaned off interpretations on the left of the above chart and nudged towards interpretations on the right.

Technical versus Adaptive interpretations

One of the first tasks of leadership — and by leadership, I mean anyone with some sort of formal or informal influence — is to educate others that adaptive challenges are fundamentally different from technical ones.

Technical challenges are those with known solutions. If we want to build a bridge across a river, then we can commission an engineering company to design it and a construction company to build it.

Adaptive challenges, like the pandemic-induced challenges our organisations are currently facing, do not come with a set of blueprints. We can not call on experts or refer to historical precedents for guidance. We are navigating uncharted territory. We have to learn to adapt the best we can. We have to think hard, explore, experiment, collaborate, discover, remain agile, and take tentative but brave steps into the future.

It is important to guard against default technical thinking when dealing with the adaptive aspects of a challenge. If people are rushing to conclusions, or wanting to defer decisions to authority figures, experts, or consultants, or being blasé about the gravity of the problem, then these are signs that an adaptive challenge has been misinterpreted as a technical one.

In this case, leaders need to nudge the group into a learning modality. They might ask questions such as, “perhaps this is a problem that a consultant can not fix?” or “what if this interpretation is all wrong? How would ‘X’ interpret it?”.

The learning modality should continue until a sense of coherence has been reached, a sense that all alternative perspectives have been properly considered and integrated into a shared interpretation that can be acted on, even if tentatively.

Benign versus Conflictual interpretations

Aversion to conflict spawns reassuring utterances and benign strategies. Weak ‘peacetime’ leaders will choose words to pacify people and come up with ways to avoid conflicts and confrontations. But in adaptive challenges, avoiding the harsh realities of a situation is cowardly and usually ends up fuelling crises.

It is better to surface the conflictual aspects of a problem early so they can be worked through before they become a crisis. What will the losses due to a particular strategy be? Who will be the causalities? How will they react? Which losses are negotiable and which are not? Adaptive challenges require brave conversations, and the sooner they happen, the better.

If people are avoiding the conflictual dimensions of the situation, then leaders can stimulate dialogue by asking questions such as: “who are the key stakeholders in this situation, and how might they be positively or negatively affected? How would they interpret the situation? How high are the stakes from their perspective?”

Individual versus Systemic interpretations

We often attribute organisational problems to individuals rather than see them as systemic issues. For example, statements such as “if only our department head would provide clearer direction … ” ignores potential systemic issues such as the pressures and constraints of that role, a lack of initiative from the staff in seeking clarity or offering support, poor communication networks and rituals, overly-bureaucratic norms, etcetera.

Changing the locus of interpretation to the system will allow patterns and leverage points that can affect real change to be identified. Factors such as political networks, structural bottlenecks, and norm dynamics can come into view.

Leaders can shift the focus of attention onto systemic issues through questions such as: “if ‘X’ was replaced, would the pattern just continue, and if so, why?” or simply, “what structural or systemic forces might be at play here?”.

In summary, VUCA environments require collective sense-making and decision-making. This is a deeply dialogical process where each participant is not merely talking and listening to each other but trying as hard as they can to understand each other’s interpretations, to experience each other’s reality as much as possible, and hold their own interpretations lightly enough to allow a new, more collective, reality to emerge.

Leadership is the practice of catalysing this dynamic through courageous, status quo-busting inquiry.

Posted by John Dobbin.

Post Bureaucracy

Learn more:

Much of this article was drawn from Chapter 8 of The Practice of Adaptive Leadership, a textbook that I highly recommend if you are involved in leadership at any level.

1. Heifetz, R., Grashow, A. and Linsky, M. 2009, 'The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World', Harvard Business Press

Image credits:

Locus of Interpretation — my slides, adapted from Heifetz et al, 2009

Thank you!

Your details have been submitted and we will be in touch.